Back in the early days of cell phones in these United States, cellular phones were purchased from the carrier along with a service plan. Those plans came with ridiculous pricing by today’s standards – some cost more than US$5 per minute! If you needed to replace your phone (if it was lost, stolen, broken, or even if you wanted to upgrade) you had to go back to your carrier and have them update your account to point the new device. Each device had a unique ID assigned to it, so this process wasn’t particularly difficult, just inconvenient and fairly time consuming as you were forced through whatever hoops your carrier put you though.

Eventually the GSM standard began to take hold. Networks using this standard favored Subscriber Identity Modules over device IDs. SIMs, as they’re called, could be removed from one phone and placed into a new phone. The network would see that and all calls after the swap would be routed to the new phone instead of the old one. This opened the door for bringing your own device to your carrier’s network and dramatically expanded the devices being offered to use on GSM networks.

SIMs are basically an integrated circuit (IC) built with the purpose of securely storing the international mobile subscriber identity (IMSI) and the related key that’s used to identify subscribers on mobile devices – not just phones, but tablets and computers, too.

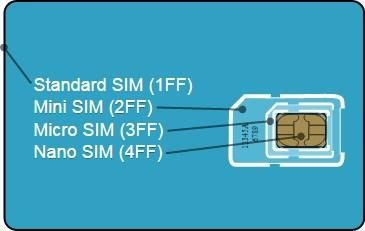

Originally, the SIM circuit was part of the “smart card” standard, a credit-card sized piece of plastic with the chip integrated into it. Since that implementation SIMs have gotten smaller, progressing through mini, micro, and now nano sizes – the latter being about the size of a fingernail.

Still needed?

With all the advances we’ve seen in mobile telephony since the SIM was created, why do we still need them?

These days sims usually require a spring-loaded slot or even a tray (and corresponding tray ejector tool) to be constructed into or included with all our devices. While these components cost only a few cents, they dictate (to a certain degree) how thick our phones are, how waterproof they are, and they ultimately occupy space that could be used for something else – or omitted altogether.

Why can’t we simply solder a SIM into our mobile devices? Thanks to a standard called Embedded-SIM (or Embedded Universal Integrated Circuit Card – eUICC), manufacturers can do just that. They’re not typically used in consumer products, but the equipment exists.

Our phones and tablets all have unique numbers assigned to them, why not simply program the SIM “stuff” into the chips that already are included in our devices? That could be done, too – in theory. CDMA devices already do that today (ala Sprint and Verizon), but even those companies are adopting – not moving away from – including SIMs in devices authorized for use on their networks.

SIMs are a good thing

With my non-locked Nexus 6 (I prefer “non-locked” rather than “unlocked” because my phone has never been “locked”), I can pop in a T-Mobile SIM and use it on T-Mobile, or an AT&T SIM and use it on AT&T, or a MetroPCS SIM and use it on and use it on MetroPCS, or any SIM from a GSM provider that uses the bands supported by my phone.

Thanks to today’s advanced SoCs I can even pop a Verizon or Sprint SIM into my Nexus 6 and use my phone on those carriers. Michael Fisher just told us about his experiences finding and using a local SIM when he travels overseas on business (and why T-Mobile is making that less necessary).

Now, with Google’s Project Fi, a customer can get a SIM that uses multiple networks (T-Mobile, Sprint, and even WiFi in this case) to give you the best service available in whatever area you’re in.

Although we may not need SIM cards any more, the benefits they offer far outweigh the additional cost of including the hardware to support them.

Long live the SIM!