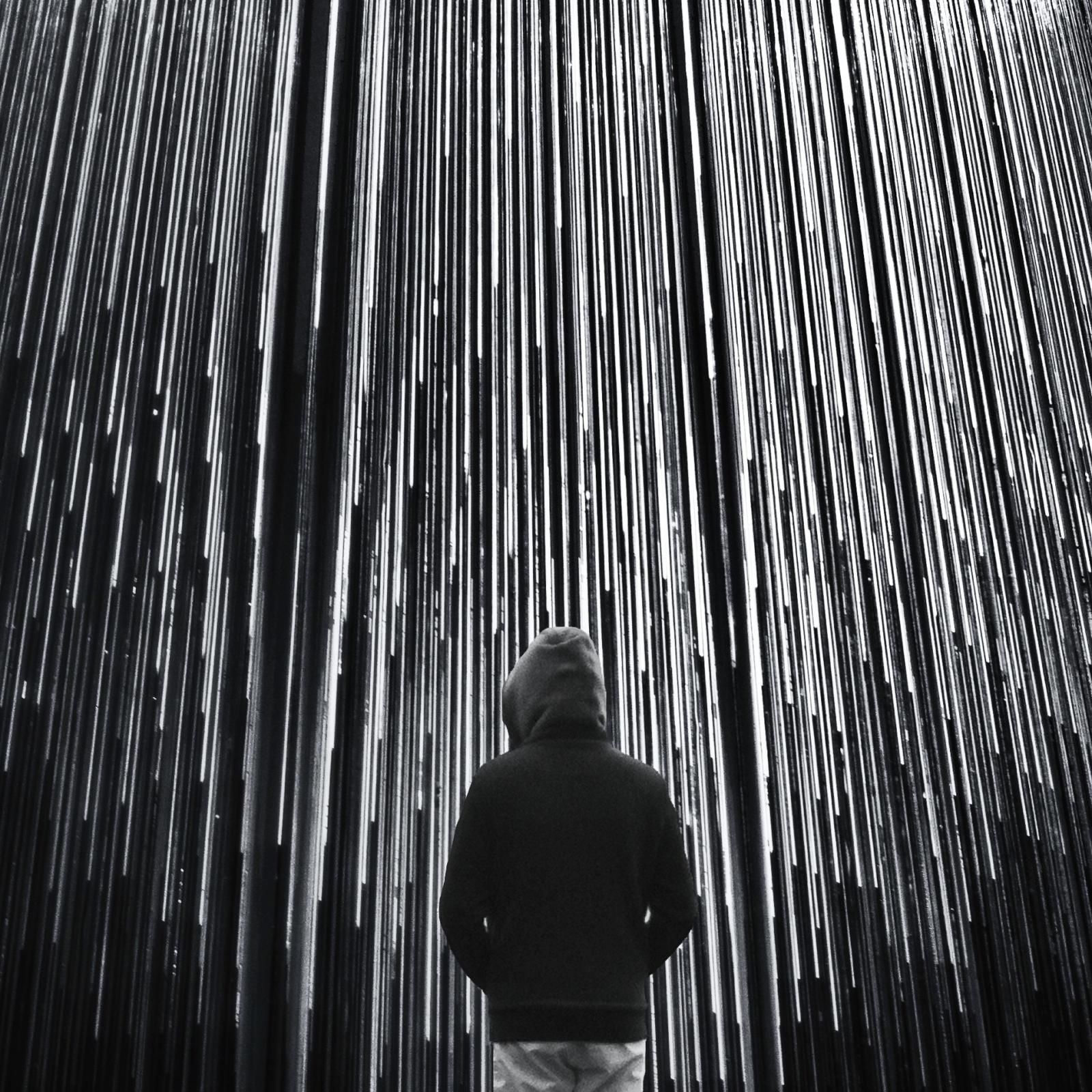

Image credit, left to right: John Gamble; Clay Butch Benskin; Helen Breznik

•

Since its invention, photography has gone from being a complex craft mastered only by experienced professionals to being easily accessible to all. Pretty much everyone these days carries a smartphone in their pocket, with an always ready-for-action camera.

The rise of mobile photography and the ability to shoot and share instantaneously has revolutionized the field and created what has been called a ‘democratization of photography’. While many are still wondering about the possible implications of the mobile-age on photography as a profession, people like Daniel Berman, creator of the Mobile Photography Awards, are actively seeking to establish a worldwide recognition of mobile photography as a form of art. We sat down with Daniel to ask him a few questions about the MPA’s, mobile photography and its future.

Pocketnow: Tell us a bit about yourself, Daniel: your background and your artistic journey.

Daniel Berman: Thanks for the opportunity to chat. I grew up in Toronto, Canada and now live just outside the city with my family. I’ve spent most of the last 15 years running my own company as a director and producer of documentaries, music specials and nature programs for a variety of international television broadcasters. I love working with images because at heart I’m a storyteller – whether that involves moving images or taking photos, my goal is always to try and convey some fundamental kernel of a story. when I was six years old I made my first pinhole camera out of cardboard and have been shooting ever since. I’ve always had a camera throughout my life, one way or another.

P: How did you become interested in mobile photography and at what point did it become more than a hobby?

DB: As a film maker, I’m always around cameras, so shooting with my phone became just another camera. As time went by, and more and better photo apps came along, I had even more fun making images this way. Here are a couple of examples – one where a “moment” is captured, which, for me, proved Chase Jarvis’ adage that the best camera is the one we have with us. The other image is one I spent time manipulating for many days until I hit upon something I liked. It’s a purely graphic creation, hardly related to the actual photograph. That image made me a believer in the future of the phone as an artistic device, limited only by the imaginations of the app developers and the users.

I felt there was a big leap in mobile photography when the iPhone3GS introduced the touch-to-focus feature. Around the same time, developers really stepped up the game with photo apps, and all of a sudden it was clear that here was something with awesome creative potential for photography and image making in general. I loved it. Shoot, edit, share. Interact with people in real time from all over the planet. One device. Clearly, many, many people felt the same rush, but the social networks lagged. And so, Instagram came along and at that time offered the most elegant solution, a walled garden community built around shooting, editing and sharing.

P: What motivated you to create the Mobile Photo Awards?

DB: Being involved in the community early on I witnessed the Wild West side of mobile photography’s early years. Prior to Instagram, even before Hipstamatic, we could sense the excitement around the possibilities of shooting, editing and sharing from one device. I wanted to bring recognition to some of the best artists and the finest images being created with these remarkable devices. I also realize that for an exhibition to be taken seriously in the fine-art space, to be invited to art fairs and established galleries with an active clientele, the images need to be part of something larger, and that’s exactly what the MPA does.

The MPA isn’t really about having your “winning” image on a website with a stamp on it. The MPA is an opportunity for people to bring attention to their work at the same time as we bring attention to the work of the community as a whole. We are a combination of an open gallery call and a competition. The amount of press and interest we generate outside of the mobile world is a result of presenting a coherent set of fine art exhibits that go beyond one person’s taste.

P: Tell us more about the contest. When is it open for entries? What are the rules, how does the judging process work and what are the prizes?

DB: We run open calls for exhibits throughout the year with the big competition open for two months each autumn, October-November. Check our website www.mobilephotoawards.com to see what we have going on at any given time. Each year we award a $3,000 grand prize and two $500 awards, one for 2nd place and one for top photo essay. In the short time since its founding, the MPA has distributed more than $35,000 directly to artists and photographers through cash prizes and fine-art sales from our exhibits.

As for rules, the main stipulation is that images entered must be shot and processed on mobile devices (phones and tablets). No computer manipulation and no non-mobile cameras are allowed. The rest of the rules are pretty much in line with every other competition and open gallery call for art exhibits, i.e. there is an entry fee, you must enter your own images, enter before the deadline, etc. We have multiple categories to enter like Black & White, Still Life, Street Photography all the way to Visual FX, Digital Fine Art, and a cool new category called The Darkness, for shadowy and noir-inspired images. A complete list is found on the website and you can also visit our FAQ for more information.

P: With so many beautiful entries, it must be tough to choose the best ones. What do the judges generally look for in the winning photo?

DB: We look for images and artists that speak to the viewer, tell a story and offer a new perspective on a familiar subject. The goal is to find those pictures that transcend the medium itself; pictures that are meaningful in their own right. Above all, we look for artists who have a clear, distinct and compelling vision.

P: Thousands of images from around the globe are submitted to the contest. Did you ever expect it to become so big?

DB: We’ve always known the interest is out there. That seems clear. Our numbers have increased each year exponentially. This year we had over 7,000 images from nearly 1,200 photographers from more than 65 countries. Our goal is not to reach specific numbers but to seek as many inspiring images as possible. As more images are entered from around the world we continue to see new subjects, fresh colors, and new approaches to the art form, and that’s exciting to us.

P: It seems like most people still don’t take mobile photography too seriously. What feedback are you getting from the fine-art community?

DB: Often, if we’re at an art fair, we might be next to the Pace Gallery, or just down a few spots from some Warhols and a Lichtenstein going for 6 figures. People come to us with no expectations, they see beautiful pictures on a wall, framed and for sale, and they look, point and sometimes ask questions. It’s only after 20 minutes that we mention the work was completely created on a phone, and most still do double takes. Now, sometimes people come to us and tell us they’ve read about the exhibit in the paper, or were told by a friend, another gallery owner, whatever; they know the medium and are interested in what we’re showing. I can tell you definitively that a large percentage of the images we have sold at fine art prices, have sold because the buyer really, really liked the picture. If the artist is good, the medium becomes much less important.

P: So, would you say people are gradually becoming more accepting of mobile-photography as a serious art form?

DB: In my opinion, the key here is to simply look at the images. It’s no different than any other medium, or let’s say, any other creative work so closely related to the device from which it arises. Mobile Photography is both its own thing and, at the same time, it’s connected and interrelated to a host of other artistic mediums and technology. As an art form, that all depends upon the talent, vision and persistence of the artists using the devices.

P: It’s still quite common to hear references to mobile photography as iPhoneography; why do you think it is so?

DB: In the early years, 2008-2010, the term iPhoneography was a galvanizing force – it brought together a great many people from around the world, people who were somewhat obsessed and convinced of the brilliance of a device that could shoot, edit and share from anywhere. It’s so cool, right? And 99% of those people had an iPhone. So it made sense. But, as time has progressed, the term Mobile Photography has really become the general standard. I think this has happened for obvious reasons, not the least of which is that it isn’t brand specific; it’s inclusive of all devices performing the same functions. When photo apps like VSCO or social networks like Instagram are available cross-platform or when competitions seek mobile photos, etc., it makes little sense to limit the scope of how big this really is to one device.

The term iPhoneography is still in use and describes quite well a niche or genre within Mobile Photography in general. If someone wants to call themselves a practitioner of iPhoneography that’s totally cool with me, it means they do their mobile photography with an iPhone. It didn’t have much shelf life as a kind of “Kleenex” or “Band-Aid” – iPhonegraphy doesn’t really work as a universal, overarching branded term for “all” mobile photography.

P: Where do you think mobile photography is headed, and what are your thoughts on its influence on professional photographers and the visual arts in general?

DB: The tension isn’t so much between professional photographers and mobile photographers – there doesn’t have to be the distinction. Mobile is a tool for everybody and anybody who finds it useful. It’s true that in some areas jobs are being lost. In other areas, new jobs are being created. Economies are fluid and a sudden adoption of new technology often forces change in a particular industry at a pace too rapid for some people. I’ve said all along that the instant gratification and real-time feedback of the shoot/edit/share model would cause a disruption across any number of professions. We see that already with new categories, where brands partner with photographers to leverage their following, often in real time. I see hiring a photographer simply for their social influence as perfectly fine. It’s a marketing stunt. Those gigs didn’t exist 5 years ago.

The tech itself will cannibalize parts of the camera industry and forever change certain product categories. It’s already happening. We see Canon, Nikon, Fuji and others finally incorporating Wi-Fi into their new models. This allows a quick transfer of images to a smartphone, for editing and sharing. Like a reverse Trojan horse! Increasingly, the smart phone and the tablet are becoming the “hub” where our pictures come and go, regardless of which camera we use. What I absolutely do not see is a diminished need for professional, high-quality image making. Those who adapt will thrive.

Daniel can be found on Instagram and Twitter: @reservoir_dan