CES 2013 was many things: a beacon of hope offering tons of potential for the new year in tech; a smorgasbord of cool devices and odd offerings to drool over; and, to hardware-hungry mobile mavens like me, something of a disappointment overall.

Still, there was enough newsworthy content for the Pocketnow team to generate over 30 videos packed with mobile-tech reporting. And in the process of shoving all those frames into the YouTubes, we became well-acquainted with the constraints of mobile data networks. Amid the throng of over a hundred thousand people trying to do the exact same thing we were -upload content to the internet- we found sharing the news with you to be a daily challenge.

This wasn't a total surprise: Anton and I had experienced this problem at IFA, using Berlin's HSPA networks. Common sense dictates that when you're immersed in a sea of humanity, with everyone feverishly flicking away at their mobile devices, you're going to run into a connectivity problem or ten. But I'd thought -perhaps naively- that the 4G LTE networks blanketing Las Vegas would save us from some of that inconvenience at CES. We came equipped with a boatload of devices ready and willing to connect to the next-generation networks operated by Verizon Wireless and AT&T Mobility, but though the signal bars were willing, the throughput was often weak nonexistent.

That's not a condemnation of either company, or of cellular networks overall: connecting via other cable-free means like WiFi was just as difficult. To the showrunners' credit, the various press rooms were well-stocked with hardwired ethernet connections to serve members of the media, but I found it rather absurd that, at an event at which hundreds of *wireless * devices were being showcased, we were forced to rely on physical cables to do our job.

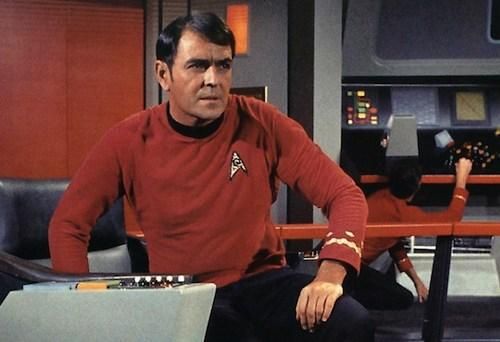

Pictured: irony.

Being in the midst of all that mobile technology, while simultaneously being cut off from using most of the features of my own mobile phone, was a strangely unsettling experience. Despite the best efforts of the so-called "Long Term Evolution" networks and Distributed Antenna Systems to bear up under the strain, we were in the dark a lot. That sucked.

To be fair, the problems would have been infinitely worse had LTE not been present at CES — as we learned in Berlin. On the whole, the cellular signal was usable more of the time in Vegas, and when it vanished, connectivity returned more quickly there than at IFA. Incredibly, the Pocketnow team was able to maintain constant connectivity using WhatsApp, a data-based messaging service, with almost no blackouts or interruptions: for us, that was probably the biggest logistical win of the show.

But as we discussed on our special CES episode of the Pocketnow Weekly podcast, transferring any meaningful amount of data over LTE was difficult anytime before 2am during our week in town, and when we were able to pitch some packets up the pipe, we found ourselves frequently running into errors, or being throttled by some mysterious force on the network side.

“He who would cross the Bridge of Bits must answer me these questions three!”

I can't say for certain whether these problems were a result of bandwidth limitations in the air interface or some backhaul choke-point, but it's probably safe to say we were looking at a combination of those very hard-to-solve issues. There's only so much available wireless spectrum, after all, and only so many slots available for users even at an efficient LTE cell site. The spectrum issue, especially in a heavily-regulated wireless landscape like the United States, is anything but an easy one to solve.

That's the problem with treating LTE as some sort of savior, or of growing too comfortable with its outrageous throughput speeds at this early stage of its deployment. We asked in a piece a few months back whether LTE networks would end up crumbling just like their 3G predecessors. The unsurprising answer, which CES proved as a sort of unscientific field test, is "absolutely," given enough of a load.

A hundred and fifty thousand added people would stress the wireless infrastructure of any city, no matter how well prepared it was for the onslaught. In no way am I suggesting that the carriers providing coverage at CES did a poor job. Rather, I'm saying that any system, no matter how advanced, can be overloaded. That was true for the old copper-based landline systems, and it's true of wireless networks today. Las Vegas served as a keen reminder that buzzwords like "4G" won't always keep the signal bars glowing on my smartphone in extreme situations, and that fancy 20Mbps throughput I presently enjoy in my low-LTE-penetration hometown won't last forever. As an article over at CNN pointed out last February, wireless connectivity is a finite resource: the microcosm we witnessed last week in Las Vegas might become an everyday reality for some customers in as soon as five years as the spectrum and capacity crunch continues, LTE or no. Avoiding that dystopia is going to depend on a combination of regulatory action from governments, more billions thrown into network maintenance by the carriers, and creative thinking on the part of companies large and small to figure out how best to shove ten pounds of internet into a five-pound bag.

In the words of Scotty, "hold on tight; it gets bumpy from here."